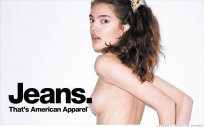

A member of staff in the US attire factory in downtown la, in February. Credit Photo by Patrick T. Fallon/Bloomberg via Getty

Paula Schneider, the new C.E.O. of American Apparel, the largest attire maker in the United States, is within a difficult place. The organization is carrying hundreds of millions of dollars in debt, and its own stock cost and product sales tend to be falling. A July 6th S.E.C. filing because of the company describes “a host of legacy issues, ” notably the “approximately 20 lawsuits and administrative actions initiated by Company founder Dov Charney and his associates.” Charney had been fired “for cause” last December, after becoming suspended in the aftermath of sexual-misconduct allegations. At the time, the company had already lost above 300 million bucks in 5 years, along withn’t turned a profit since 2009. This present year, in the 1st quarter of 2015, web product sales decreased nine per cent in contrast to exactly the same duration the year before, despite an enormous sale when, Schneider informed Apparel Information, a million pieces “flew from home.”

Charney raised United states Apparel to prominence by selling a liberal worldview that combined intercourse appeal with a made-in-America ethos that based on the truth that, considering that the nineteen-nineties, the vast majority of the business’s wares have-been manufactured in a factory in la by a virtually totally Hispanic workforce. Since overpowering as C.E.O., in January, Schneider has actually focused on basics, talking in interviews about attempting to increase sales, specially online—and by streamlining the organization’s stock to jettison unpopular types, closing the essential ineffective of the 2 hundred and forty or more areas, and starting brand-new stores much more attractive places. With regards to the business’s picture, she has emphasized her purpose to really make the brand name less sexualized; she's additionally stated your sweatshop-free model is vital and will also be maintained. Thus far, however, the greater considerable activity your business has had since Schneider became C.E.O. has been to cut back its staff. In April, United states Apparel let go about 100 and eighty workers, a lot of them in manufacturing. In early July, more slices had been launched, many apparently in management and retail. These layoffs raise a concern, the implications of which exceed United states Apparel: Can a mass-market manner organization contend with companies that will offer comparable items at reduced costs by counting on inexpensive offshore work?

Currently, ninety-seven per cent of attire offered in the U.S. is manufactured in international production facilities, in which employees are often compensated acutely low earnings and sometimes toil in dangerous problems. A lot of the rest of the three percent of clothing is part of the “luxury products” marketplace. Considerably was discussed the luxury sector’s reliance upon exclusivity and advertising, yet additionally it is marked by competent and precisely paid production (though, definitely, many companies identified and listed as luxury also make use of sweatshop labor). The label The Row, for example, which creates at the least a few of its products at the InStyle factory, in new york’s apparel region, charges significantly more than six hundred bucks for a pair of trousers. Raleigh Denim, a small company that produces its clothing in new york, fees between one hundred and seventy-six dollars and 300 and eighty-five dollars for a pair of pants. In contrast, United states Apparel’s costs look extremely ambitious—the business charges just forty-eight bucks for the Rayon Challis Brunch Pant, while its jeans retail for between seventy-four and one hundred and forty dollars.

At those price points, American Apparel is competing with chains like Uniqlo, Gap, and H&M, who outsource their production to Bangladesh, China, Vietnam, and other countries with poor labor records. H&M charges $5.95 for a fundamental men’s T-shirt, while American Apparel fees sixteen bucks. To put this price difference into context, in 2005 the Institute for worldwide Labour and Human liberties estimated the cost of a long-sleeved shirt produced in Bangladesh is $4.70, which $0.22 was labor expenses and $3.30 went toward materials. The figures tend to be comparable for Southeast Asia. The cost when you look at the U.S. was $13.22, with around five dollars for natural material and $7.47 for labor. When confronted with proof poor production circumstances (such as for instance wage cheating, exorbitant hours, poor ventilation, and overcrowding), it has become common for fashion stores to proclaim lack of knowledge due to their particular outsourcing of management and services. American Apparel, meanwhile, boasts about its vertical integration, and about professionals and manufacturing crews just who work with the same building complex.