Before the development of synthetic fabrics with their built-in water-resistant properties, men had to waterproof their clothing and gear from without, using a variety of natural substances like grease, tannins, beeswax, soap, and tar. For obvious reasons, early mariners had the keenest interest in developing effective waterproofing methods. Sailors of the 16th century would apply grease and fish oils to their sailcloths, which would make them more efficient because they caught and “reflected” the wind versus just absorbing it. The mariners would then cut wind and waterproof capes for themselves from the remnants of the sails, creating garments that kept them from being soaked through as waves splashed over the deck.

Before the development of synthetic fabrics with their built-in water-resistant properties, men had to waterproof their clothing and gear from without, using a variety of natural substances like grease, tannins, beeswax, soap, and tar. For obvious reasons, early mariners had the keenest interest in developing effective waterproofing methods. Sailors of the 16th century would apply grease and fish oils to their sailcloths, which would make them more efficient because they caught and “reflected” the wind versus just absorbing it. The mariners would then cut wind and waterproof capes for themselves from the remnants of the sails, creating garments that kept them from being soaked through as waves splashed over the deck.

As the centuries progressed, pioneers and travelers of all stripes tested other waterproofing substances in the field and tweaked their formulas. During the 19th century, a wax made primarily of paraffin (a substance derived from petroleum) was developed that was extremely waterproof and windproof and wouldn’t become stiff and yellow like previous waxes did when melded with fabric. While the first waxed cotton products started appearing in the mid-1800s or so, it wasn’t until the 1920s that manufacturers started to perfect the process. Outdoorsmen of the early 20th century swore by waxed canvas and used it to craft their tents, Dopp kits, pants, hunting jackets, tool satchels, gun cases, and sleeping bags.

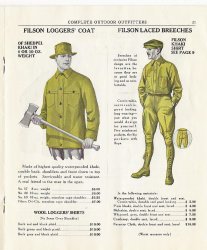

Waxed fabric is still used today in a variety of clothing and equipment, from jackets, to hats, to bags, to tents, and more. Beyond the practical benefits, waxing can also give your gear a weathered and vintage look. High-end clothing companies like Filson and Barbour sell some very nice-looking waxed items, but they’re also very expensive. Lucky for you, you can do your own waxing at home for about $15, and come away with windproof and waterproof clothing and gear.

Waxed fabric is still used today in a variety of clothing and equipment, from jackets, to hats, to bags, to tents, and more. Beyond the practical benefits, waxing can also give your gear a weathered and vintage look. High-end clothing companies like Filson and Barbour sell some very nice-looking waxed items, but they’re also very expensive. Lucky for you, you can do your own waxing at home for about $15, and come away with windproof and waterproof clothing and gear.

Here’s how to do it.

Supplies

A Note On Supplies

Wax — Using paraffin is definitely the old school way to go, but it has it downsides. Filson, for instance, makes a paraffin wax, though it’s specifically for maintaining already waxed items. Sure, you can apply it to your non-waxed clothing, but you won’t get the same result, and the application is a bit more difficult and involved.

Wax — Using paraffin is definitely the old school way to go, but it has it downsides. Filson, for instance, makes a paraffin wax, though it’s specifically for maintaining already waxed items. Sure, you can apply it to your non-waxed clothing, but you won’t get the same result, and the application is a bit more difficult and involved.

For these reasons, I decided on using Otter Wax (we have no affiliation, nor is this an ad). It’s the only natural waxing product out there, which appealed to me. It’s also specially formulated to treat and waterproof non-waxed items and has the easiest application process of any product out there, as you’ll see below. It’s also the only wax carried and endorsed by Huckberry, so you know it’s a winner.

Clothing/Gear — While the wax is theoretically made for canvas fabric items (like the bag above), it can be used on virtually any material. It should go without saying, but if you want an item of clothing to remain breathable, waxing is not the way to go, as it will seal up the fabric’s pores of ventilation.

I tested three materials, and while they certainly had different cosmetic effects, the end result of being windproof and waterproof was the same across the board. Try it on flannel (warning — flannel and wool will look much different after waxing), your canvas tent, your camera bag — whatever you want.

I tested three materials, and while they certainly had different cosmetic effects, the end result of being windproof and waterproof was the same across the board. Try it on flannel (warning — flannel and wool will look much different after waxing), your canvas tent, your camera bag — whatever you want.

If you’re worried about how the wax will affect the appearance of the item, test the wax on a small and inconspicuous piece of fabric before diving in.

Before you get started, be sure your items are clean and dry.

Caring For Your Waxed Items